The past two weeks in California have been scorching, with temperatures consistently over 100°F. Outdoor photography is challenging under the harsh sunlight and heat.

When life gives you lemons, slice them and put them under a lightpad. Home photography under controlled light and in the air conditioning is better than no photography, and I have a project: augment my GeoGalleries Summer collection, which features images in high key. And for that, I have been using a LED light pad.

What is a Light Pad?

A light pad is a flat, illuminated surface emitting consistent, even light. Designed originally for artists to trace images, it has found a unique place in photography. It is thin, portable, and comes in various sizes and brightness levels, providing a steady backlight for objects. Below is a photo of my Light pad, with the subject of today’s blog post, placed on top of it.

Benefits of Using a Light Pad in Photography

- Consistent Lighting

Light pads provide steady illumination, unlike unpredictable natural light. This consistency is crucial for product, flat lay, and macro photography.

2. Enhanced Details

Backlighting from a light pad highlights intricate details in delicate items like jewelry, flowers, or insects, revealing textures and making subjects stand out.

3. Versatility

Light pads add a creative touch to various types of photography, from food to still life. They are also useful for tracing and transferring images, handy for photographers who enjoy drawing or painting.

4. Portability

Their slim design and portability make light pads easy to carry and set up, whether in a studio or on location.

Photographing Translucent Subjects

Photographing translucent subjects like leaves can be challenging with traditional lighting. A light pad provides perfect backlighting, emphasizing the subject’s translucent qualities. This technique is particularly effective in botanical photography.

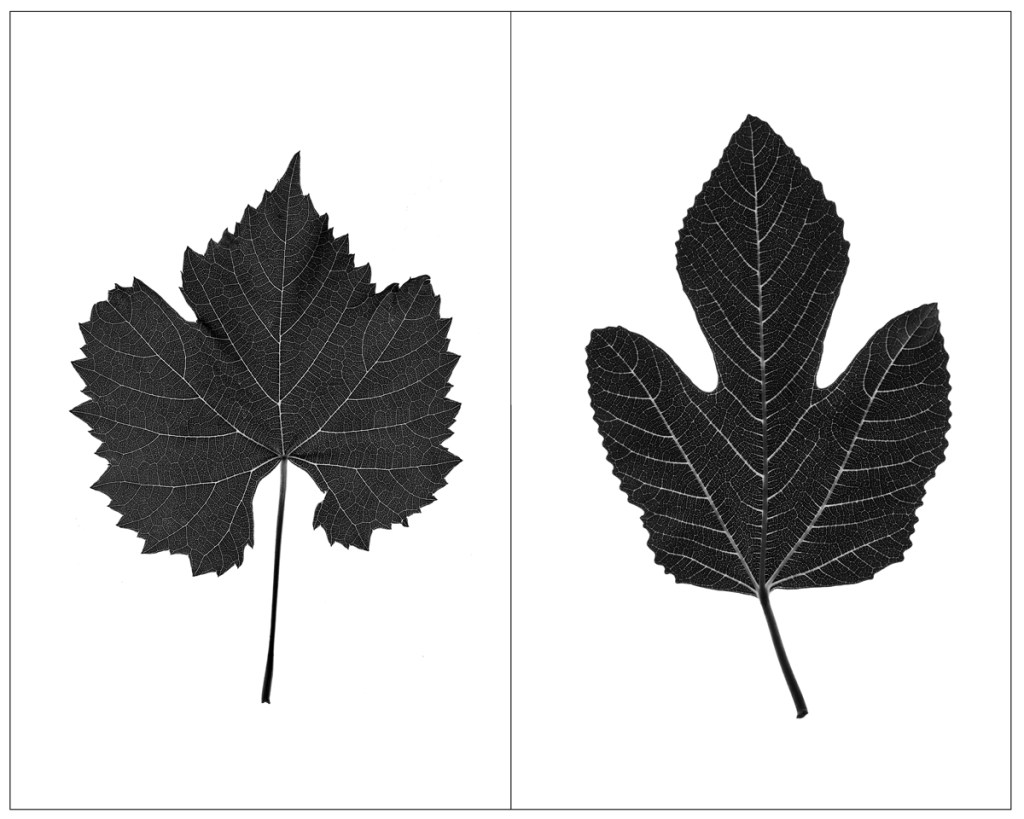

For example, the FEATURED PHOTOGRAPH (f/14, 1/125s, ISO 640), repeated below for convenience, showcases a great leaf (left side) and a ficus tree leaf. The technique is simple: place the leaf on the light pad, turn it on, and photograph it from above. I used a 50 mm prime lens mounted on a tripod for stability.

Tips for Using a Light Pad in Photography

- Adjust Brightness: Experiment with different brightness levels to achieve the desired effect.

- Combine with Other Light Sources: Adding other light sources can create depth and dimension. The photo below was obtained with a strobe facing the ceiling to add some light on the trip-dimensional heads of the grass stalks.

- Use a tripod: if you are photographing indoors, it is possible that the light coming from the pad isn’t enough to keep a shutter speed that is consistent with sharpness, if you are using a longer lens. A tripos eliminates the need to worry about motion blur.

Conclusion

Incorporating a light pad into your photography is a cheap, easy and efficient way to produce botanical photographs on white background, highlighting the translucent parts of the subjects.

______________________________

Wall Art landscapes and miscellaneous

________________________________

Leave a reply to Alessandra Chaves Cancel reply